Class 5: Adversarial Machine Learning in Non-Image Domains

Beyond Images

While the bulk of adversarial machine learning work has focused on image classification, ML is being used for a vartiety of tasks in the real world and attacks (and defenses) for different domains need to be tailored to the purpose of the ML process. Among the most significant uses of ML are natural language processing and voice recognition. Within these fields, attacks look very different from those on images. With images, individual pixels can be changed large amounts without making the image unrecognizable, whereas in voice recognition, the audio needs to remain smooth, but many transformations can be done that are not noticable to humans. These attacks are becoming more and more significant as always active listening devices like Amazon Alexa are becoming more common in the public sector. A broadcast television attack could be used to access personal accounts and devices of thousands of people simultaneously without many of those being attacked even noticing.

Adversarial Audio

Nicholas Carlini and David Wagner. Audio Adversarial Examples: Targeted Attacks on Speech-to-Text. University of California, Berkeley. 5 January 2018. [PDF]

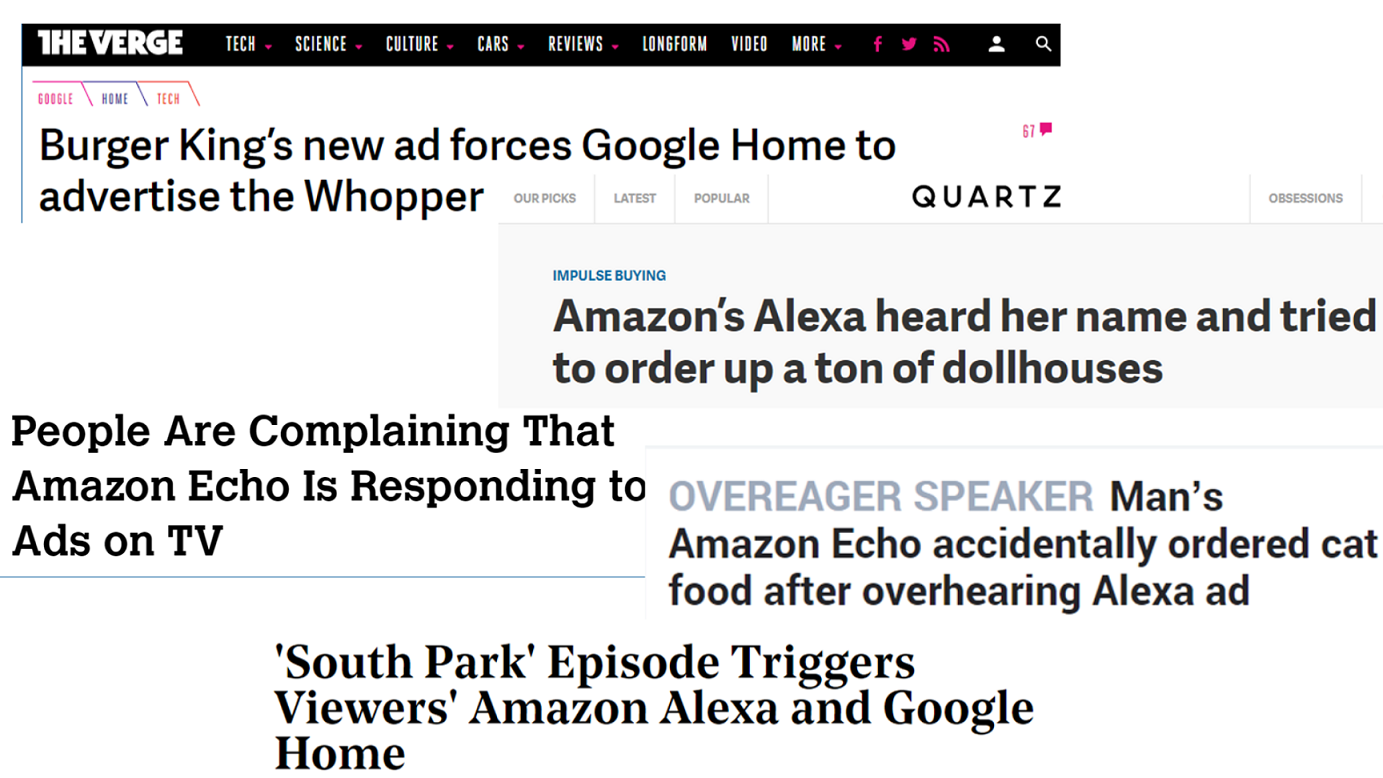

If classic science fiction authors, painting grandiose visions of artificial intelligence in the future, could read some of the tech headlines of today, they might be surprised by how their predictions panned out:

These news articles recount recent incidents in which smart home voice-controlled devices have been activated by voices in television advertisements and shows, rather than from a physically-present human voice. While these untargeted, accidental (we assume) occurrences perhaps make for amusing news, they reflect a significant potential vulnerability in speech-to-text systems against targeted, adversarial attacks.

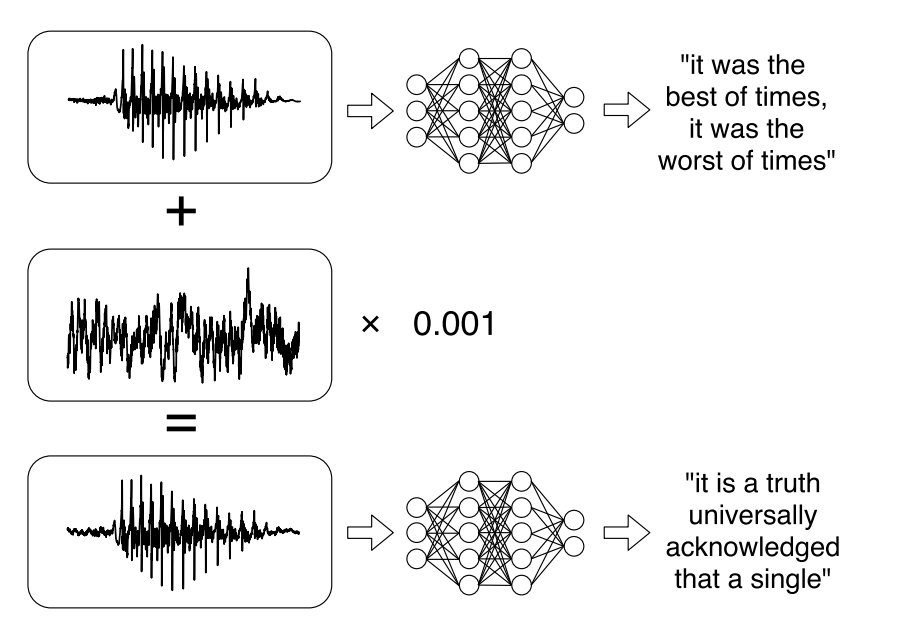

In their 2018 paper, authors Carlini and Wagner develop and demonstrate a white-box attack against automated speech recognition systems: “given any audio waveform, we can produce another that is over 99.9% similar, but transcribes as any phrase of choice”. That is, a virtually unaltered sample, which might sound, at worst, noisy or mildly distorted to human ears, will be translated as an entirely different set of characters by the system.

Audio distortion

The goal of this attack is twofold: (a) to add the least possible amount of distortion to the original audio, and (b) to cause the distorted audio to map to an arbitrary sequence of transcribed characters. This thus becomes an optimization problem.

To measure distortion, we use \(dB(v)\) to represent the loudness of a given sample \(v\) measured in decibels. First, let the change between the original and distorted samples be

$$dB_x(\delta) := dB(\delta) - dB(x)$$

where \(x\) is original and \(\delta\) distorted. Then, let

$$C(v) = \mathop{\arg,\max}\limits_p Pr[p | f(v)]$$

be the most likely transcribed phrase given some sample \(v\).

Our optimization problem becomes thus:

$$\text{minimize } dB_x(\delta)$$ $$\text{such that } C(x+\delta)=t$$ $$\text{with } x+\delta \in [-M,M]$$

where \(t\) is the target transcribed phrase and \(M\) is the maximum representable value (no distorted samples that are out of range – in the authors’ case, this happens to be \(2^{15}\) dB)).

However, due to the nonlinearity of \(C(\cdot)\), gradient descent fails, so instead we minimize

$$dB_x(\delta) + C(\cdot) \cdot \ell(x+\delta,t)$$ $$\text{with } \ell(x’,t) = \text{CTC-Loss}(x’,t)$$

where the \(\text{CTC-Loss}\) (Connectionist Temporal Classification Loss) function is just the negative log-likelihood function.

After solving this optimization problem, the authors constructed targeted examples on the first 100 test instances of Mozilla’s Common Voice dataset, attempting to distort 10 of these to achieve 10 target incorrect transcriptions – with 100% success for source-target pairs, and a mean perturbation magnititude of -31 dB.

Even after changing the loss function to

$$\ell(x,pi) = \sum_i \max (f(x)^i_{\pi^i}-\max_{t’\neq \pi^i} f(x)^i_{t’},0) $$

which avoids reducing loss and forces it to be more strongly classified, the mean distortion was only reduced from -31 dB to -38 dB, still a barely-noticeable to unnoticeable change.

Attack Sources and Targets

Attack models worked consistently regardless of context, meaning that an attack using white noise or non-speech is as easy to craft as one using speech. Targeting silence turned out to be even easier than targeting speech.

Robustness

Random pointwise noise of less than -30dB is sufficient to corrupt an attack; although stronger attacks can be crafted using larger dB changes. The attacks did manage to be MP3 resistent, which speaks to the minimization of loss in MP3 compression as well as the fidelity of the attack model.

These attacks do become easier with longer sources, as the pacing of the target speech can be varied more, giving a larger attack space in which to work. In an ideal case for an attacker, they would be working with a prerecorded broadcast, which gives them a large continuous space to attack. That said, Over-The-Air attacks were not viable due to the white noise and variation in speakers and the rooms. Hidden voice commands did, however, show some promise for broadcast attacks.

Transferability was shown to hold, as it is somewhat fundamental to ML systems. As of yet, defence techniques on the ML layers have not yet been developed, although random noise added post-attack is a viable defence.

Natural Language Processing

Suranjana Samanta and Sameep Mehta. Towards Crafting Text Adversarial Samples. 2017.

Adversarial samples are strategically modified samples, which are crafted with the purpose of fooling a classifier at hand. Although most of the prior works have been focused on synthesizing adversarial samples in the image domain, NLP based text classifiers can also be the focal point of such exploit. This paper introduces a method of crafting adversarial text samples by modification of the original samples. To be precise, the authors propose to modify the original text samples by deleting or replacing the important words in the text or by introducing new words in the text sample. While crafting adversarial samples, the paper focuses on generating meaningful sentences which can pass off as legitimate from language viewpoint.

Approach

Initially, the authors calculate contribution of each word towards determining the class-label. A word in the text is highly contributing if its removal from the text is going to change the class probability value to a large extent. In their proposed approach, modification of the sample text by considering each word at a time, in the order of the ranking based on the class-contribution factor. For the modification purpose, a candidate pool for each word in sample text is created considering synonyms and typos of each of the words as well as the genre or sub-category specific keywords. The assumption behind choosing sub-category or genre-specific keywords based on the fact that certain words may contribute to positive sentiment for a particular genre but can emphasis negative sentiment for other kind of genre. For example, we can consider the sentence, “The movie was hilarious”. This indicates a positive sentiment for a comedy movie. But the same sentence denotes a negative sentiment for a horror movie. Thus, the word ‘hilarious’ contributes to the sentiment of the review based on the genre of the movie. Finally, replacement, addition or removal of words are performed on a given text sample at each iteration, so that the modified sample flips its class label.

Experiments

The paper performs their experimental results on two datasets: IMDB movie review dataset for sentiment analysis and twitter dataset for gender classification. They compare the efficiency of their method with the existing method TextFool by measuring the accuracy of the model obtained at different configurations. For both the cases, the proposed model was generated using Convolutional Neural Network (CNN).

The figure below (taken from the paper) shows the results for IMDB dataset. From the figure, it is obvious that the proposed method of adversarial sample crafting for text is capable of synthesizing semantically correct adversarial text samples from the original text sample. In addition, the inclusion of genre specific keywords appears to increase the quality of sample crafting. This is evident from the fact the drop in accuracy of the classifier before re-training for original text sample and the adversarialy crafted text sample is more when genre specific keywords are being used.

A significant factor for evaluating the effectiveness of adversarial samples is to measure the semantic similarity between the original samples and their corresponding tainted counterparts. A lower similarity score denotes that the semantic meaning of the original and the modified samples are quite different, which is not acceptable from the language viewpoint. The authors found the average semantic similarity between the original text sample and their adversarial counterparts (for test set only) as 0.9164 and 0.9732 with and without using the genre specific keywords respectively. Although the semantic similarity between the original and their corresponding perturbed samples does decrease a bit while the genre specific keywords in the candidate pool, the number of valid adversarial samples generated increases as it can be seen from the percentage of the perturbed samples for genre specific keywords in the above figure.

Another key component for the evaluation of adversarial samples is to measure the number of changes incurred to obtain the adversarial sample. The number of changes made to craft a successful adversarial sample should be ideally low.The following figure shows a graph that indicates the number of changes required to create successful adversarial samples with and without using the genre-specific keywords. From the figure, it is evident that, if we consider same number of modifications the number of tainted sample produced using genre specific keywords for creating adversarial samples is more than that when genre specific keywords are not used.

For the Twitter dataset, the proposed method shows similar performance as the IMDB dataset.

Example

Face Recognition

Mahmood Sharif, Sruti Bhagavatula, Lujo Bauer, Michael K. Reiter. Accessorize to a Crime: Real and Stealthy Attacks on State-of-the-Art Face Recognition. ACM CCS 2016.

Face recognition and face detection algorithms are extensively used in surveillance and access control applications. This paper focuses on fooling the state-of-art machine learning algorithms that are practically deployed for these tasks. More concretely, the paper carries out two types of attacks: dodging and impersonation. In dodging, the attacker tries to conceal his/her identity, whereas, in impersonation, the attacker tries to trick the algorithm into recognizing him/her as a different target individual. The authors realize these attacks by printing a wearable glass which, upon wearing, allows the attacker to successfully launch the attacks. The glasses used in the attack are shown below.

Parikh et al. proposed the state-of-art 39 layer deep neural network trained on 2,622 celebrities which achieved an accuracy of 98.95% for the task of face detection. The authors of this paper use this model to launch their attacks.

The objective function of the deep neural network’s softmax layer is given as below:

For impersonation, the objective is to add the minimum amount of noise \(r\) in the input image \(x\) to convert the class lable to the target label \(c_t\), as given below:

For dodging, the objective is to add minimum amount of noise \(r\) in the input image \(x\) to deviate from the correct class label \(c_x\).

The noises are then carefully added to the 3D printed glasses.

Experiments

The paper launches successful dodging and impersonation attacks. Figure below shows an example of impersonation where a female celebrity (left) is classified as a male celebrity (right) by the algorithm when the glass frame is used (center).

Figure below shows an example of dodging the face detection algorithm with minor changes to the image that donot affect a normal human judgement. Left image is the original image and the center and right images are the perturbed images where the algorithm does not detect the faces.

Further results show 100% dodging success rate and very high impersonation success rate.

Summary

While the authors perform white-box attacks on the state-of-the-art face detection and face recognition algorithms, they also discuss about successfully carrying out the black-box attacks.

— Team Nematode: \

Bargav Jayaraman, Guy “Jack” Verrier, Joshua Holtzman, Max Naylor, Nan Yang, Tanmoy Sen

References

[1] Nicholas Carlini and David Wagner, “Audio Adversarial Examples: Targeted Attacks on Speech-to-Text.” January 2018.

[2] Mahmood Sharif, Sruti Bhagavatula, Lujo Bauer, and Michael K. Reiter, “Accessorize to a Crime: Real and Stealthy Attacks on State-of-the-Art Face Recognition.” October 2016.