Class 9: Adversarial Malware Detection

Evolution of the Malware Arms Race

Babak Bashari Rad, Maslin Masrom, and Suhaimi Ibrahim. Evolution of Computer Virus Concealment and Anti-Virus Techniques: A Short Survey. University Technology Malaysia. 6 April 2011. [PDF]

Since the first appearances of early malware, advances in both combating and creating viruses have analogously mirrored the general patterns of the medical battle against evolving biological virus outbreaks — as anti-virus software continually develops innovative techniques for detecting existing viruses, virus writers seek out new methods to cheat those detection systems. To understand the present state of the field and the role of machine learning in combating malware, let’s look at a brief history of how both the attacks and defenses have evolved in the malware domain.

Encrypted Viruses

At its most basic, a virus is simply a program that is designed to alter the way a computer operates and spread from one computer to another. However, to be truly effective, a virus must also conceal itself so as to replicate and infect another computer. Thus, the most primitive approach to covering the operation of the virus code, first appearing in 1988, uses encryption to change the virus body binary codes with encryption algorithms in order to make it more difficult to analyze and detect.

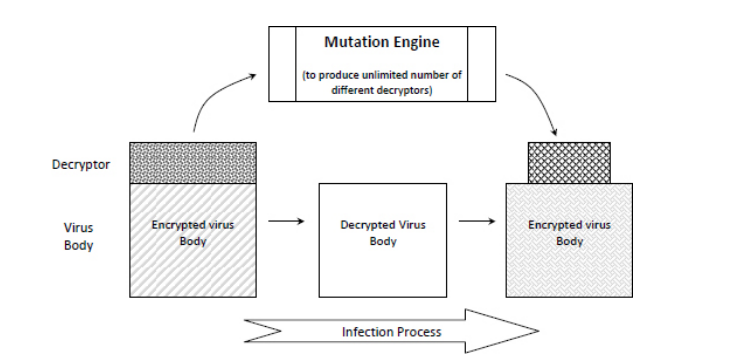

Encrypted viruses are typically made up of two parts: the encrypted body of the virus itself, and a small (unencrypted) segment of decryption code. When the infected program runs, the decryption loop executes, which first decrypts the encrypted virus code, and then moves the program control to the body of the virus code:

Encryption has utility for a virus writer in several ways; most importantly, it disguises suspicious code in order to avoid detection by static code analysis, which automatically analyzes code and generates a warning were the code simply in unencrypted plaintext. Additionally, encryption of a virus also prevents tampering - since new viruses could accidentally produced with minor changes in the original virus code, encryption ensures that an expert is required to dismantle the virus, or else run the risk of producing further harm by messing with it. Finally, an encrypted virus cannot be detected by simple string matching prior to decryption, because only the decryptor loop is identical in all variants of the virus. Thus, in an anti-virus inspection, which attempts to match the signature for an encrypted virus, the signature string is constrained and must be selected precisely.

Morphic Viruses

The constant decryptor loops turned out to be the downfall of static encrypted viruses, however; since the decryptor loop code segment remained constant in new infected files, anti-virus software had no trouble obtaining a signature string with which to seek matches in code during an inspection. To overcome this vulnerability, virus writers employed techniques to mutate the decryptor body, giving rise to a new type of concealment viruses: oligomorphic viruses.

Rather than passing on the same exact decryptor loop code for each instance of the virus, oligomorphic viruses are willing to substitute the decryptor code in new offspring of the virus when reproducing themselves. This idea is most easily implemented by providing a set of different decryptor loops rather than one, which make the detection process more difficult for signature-based scanning engines.

In fact, the most common approach in anti-virus tools is signature scanning, which uses small strings, “signatures” (the results of manual analysis of viral codes) to identify viruses and malware. The signature is meant to discover viruses in the cases of a match, thus, it is vital to ensure that any given virus signature only maps to a specific virus, rather than mapping to say, other viruses, or worse, benign programs, in order to avoid flagging non-virus code.

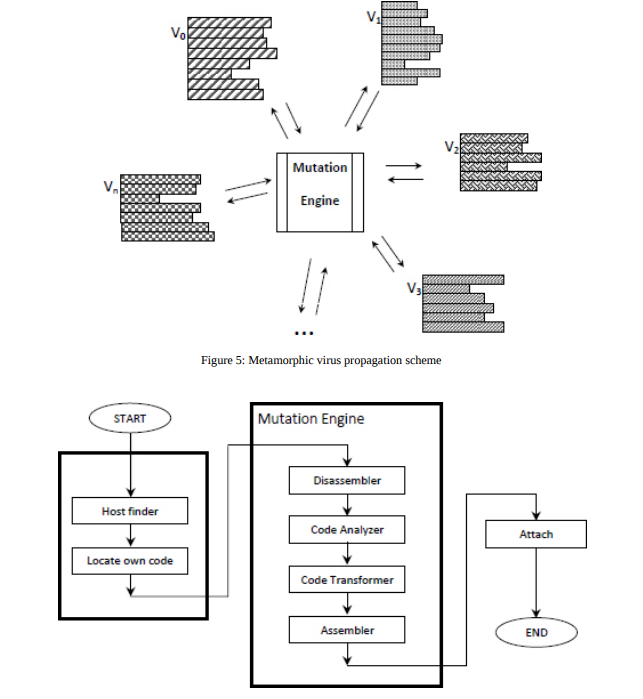

To cheat signature scanning, polymorphic viruses actually take oligomorphic viruses one step further, exploiting mutation algorithms to create a potentially infinite number of variations of decryptors in the next generation - when the virus replicates to infect a new host, it mutates its own decryptor loop to create a new permutation to pass on to the next generation. Thus, there is no consistent signature pattern from host to host that could be detected by signature scanning.

Despite these clever evasion techniques, in all the previous viruses described, once the virus body is decrypted, it is easily detected by signature scanning in its plaintext form. Polymorphic viruses, however, also dubbed “body-polymorphics”, do not even require encryption to avoid detection - instead, they mutate their entire body, rather than just their decryption loop, using the same decryptor loop-generation techniques used by polymorphic viruses to produce new instances of the virus.

Machine Learning in Malware

Konrad Rieck, Thorsten Holz, Carsten Willems, Patrick Düssel, Pavel Laskov. Learning and Classification of Malware Behavior. 15th USENIX Security Symposium. 23 April 2008. [PDF]

When an unknown malware instance is discovered, there are two important questions to be asked:

-

Does the new malware instance belong to a known malware family, or does it constitute a novel malware strain?

-

What behavioral features are discriminative for distinguishing instances of a given malware family from others?

To approach automating the discovery of the answers to this question, Rieck et al. train a classifier on honeypots and spam-traps to map unknown viruses to malware families, or to a new classification altogether, and to uncover properties that characterize families of viruses.

First, the behavior of each binary is monitored in sandbox envrionment, and behavior-based analysis reports summarizing operations. Then, the learning algorithm embeds the generated analysis reports in a high-dimensional vector space and learns a discriminative model for each malware family - that is, creates a model to predict whether this instance belongs to a known family or not, which is then aggregated against other similar models to produce a final decision. This process answers the first question.

Further, to understand and evaluate the importance of specific features for malware behavior classification, sort the weights of behavioral patterns in the learning model and consider the most prominent patterns to obtain characteristic features of each malware family.

PDF Malware Classifiers

Charles Smutz and Angelos Stavrou. Malicious PDF Detection using Metadata and Structural Features. ACSAC 2012. [PDF]

Portable Document Format (PDF)

The Portable Document Format (PDF) file structure consists of four parts: header, body, cross-reference table (CRT), and trailer. The following figures show an example PDF file, the raw content of an example PDF file, and the corresponding structural tree of the PDF file, respectively.

PDF documents have become a prevalent target of either massive or one-on-one attacks due to their wide use and diverse functionality. Popular PDF malware detectors include SL2013, Hidost, PDFRate and its variations. Among them, SL2013 and Hidost are structure-based PDF classifiers while PDFRate is content-based.

PDFRate

PDFRate, a real learning-based system introduced by George Mason University scholars Smutz and Stavrou, uses metadata and structural features to classify PDF files as benign or malicious based on the Random Forest algorithm. The feature space of PDFRate contains 202 integer, floating point and Boolean features selected from PDF metadata and file contents. Two strategies were employed during the feature selection phase, including avoiding reliance on specific byte sequence and not targeting specific known vulnerabilities. Moreover, the significant interdependence nature of the features makes the adversary’s life difficult when they attempt to control feature values. Datasets Contagio, Operational, and Community have ever been adopted in the training and evaluation of PDFRate. With respect to the classification algorithm, the number of trees is 1000 and each tree carries 43 features.

The following are the most important features for classification out of a total of 202 features: count_font count_javascript count_js count_stream_diff pos_box_max image_totalpx producer_len

Adversarial Analysis

Using PDFRate, the classification rates achieve well above 99% true positive rates while maintaining 0.2% or less false positive rates for different datasets, classification parameters and experimental conditions.

Mimicry attack, in which malicious documents are artificially modified to make some of the features similar to benign ones while retaining the malicious part, is one conceivable evasion technique. The key part the attacker want to make use of in order to spoof the defender is to mimicking the most important features for classification.

In the mimicry attack effectiveness test where the previously extracted features are purposefully modified, the six most important features were selected for evasion testing. As shown in the table below, the conclusion is that the classification error can increase to a great extent.

When the top features ranked by random forests are removed, the table below demonstrates the increase in classification error but the effect is surprisingly low. The reason is that there are many other important features retained.

The table below shows the testing results of the effectiveness of perturbation. The goal of using perturbation, i.e. increasing the feature variance by modifying the features of a malicious subset in the training set, is to reduce the importance of these features without fully negating them in order to counter evasion.

Since this approach is behavioral-based rather than signature-based, it can both identify and capture the most important behaviors of similar malware, allowing for detection that does not rely on the exact signature-matching, but rather on automated learning of behavioral patterns. This provides evidence to the claim that machine learning could provide innovative avenues into the malware field.

The findings of this study that the ensemble classifier is able to offer robust detection to counter mimicry attack even when the top features are exploited by the attacks is exciting. The classifier proves to be robust and resilient against mimicry attacks. Future directions to explore include applying the detection and classification techniques to other document types, studying the suitability of group malicious documents using the features for classification, combining other features, and performance comparative study with other techniques.

Hidost: A Static Machine-Learning-Based Detector of Malicious Files

Nedim Šrndić and Pavel Laskov. Hidost: a static machine-learning-based detector of malicious files. EURASIP Journal on Information Security, 2016. [PDF] (earlier version in NDSS 2013: [PDF])

There has been a substantial amount of work on the detection of no-executable malware which includes static, dynamic and combined methods. Although static methods perform in orders of magnitude faster, their applicability has been limited to only specific file formats. Hidost introduces the static machine-learning-based malware detection system to operate multiple file formats like pdf or swf having hierarchical document structure.

Hierarchically structured file formats

File formats are developed as a mean to store the physical representation of certain information but all of them do not have logical structure. For example, some formats like text files do not have any logical structure but others e.g.; HTML files represents a logical relationships between html elements. The following figure shows the hierarchical structure of the swf file. The pdf file structure has been discussed in the above section.

Distinguishing benign from malicious files

In a pdf structural tree, a path is defined as a sequence of edges starting in the Catalog dictionary and ending with an object of primitive type. For example, as we see in the above figure of pdf structural tree, there s a path from the root path from the root, i.e., leftmost, node through the edges named /Pages and /Count to the terminal node with the value 2. This definition of a path in the PDF document structure, which is denoted as PDF structural path, plays a central role in Hidost approach. Paths are printed as a sequence of all edge labels encountered during path traversal starting from the root node and ending in the leaf node. The path from our earlier example would be printed as /Pages/Count.

Following is a list of example structural paths of real world benign files: /Metadata /Type /Pages/Kids /OpenAction/Contents /StructTreeRoot/RoleMap /Pages/Kids/Contents/Length /OpenAction/D/Resources/ProcSet /OpenAction/D /Pages/Count /PageLayout

Presence of these structural paths in a file indicates that it is benign. Alternatively, the absence of these paths is indicative to the fact that the file may be malicious. In addition, malicious files are not likely to contain metadata in order to minimize file size, they do not jump to a page in the document when it is opened and are not well-formed so they are missing paths such as /Type and /Pages/Count. The following is a list of structural paths from real-world malicious PDF files: /AcroForm/XFA /Names/JavaScript /Names/EmbeddedFiles /Names/JavaScript/Names /Pages/Kids/Type /StructTreeRoot /OpenAction/Type /OpenAction/S /OpenAction/JS /OpenAction

System Design

The system design of Hidost consists of six stages: structure extraction, structural path consolidation, feature selection, vectorization, learning, and classification as it is illustrated in the following figure.

File structure extraction

In this stage, files are transformed into more abstract representation (logical structure) i.e.; into a structural multimap. Multimap is basically a map with associations between every structural path to the set of all leaves that lie on a given path. The concept is similar to map but you have multiple leafs as we see in path mediabox in the following figure.

Structural path consolidation

There may be cases in which semantically equivalent, but syntactically different structures can avoid detection. In Hidost, heuristic technique to consolidate structural paths to reduce polymorphic paths. For example, /Pages/Kids/Resources and /Pages/Kids/Kids/Resources can be reduced to /Pages/Resources.

Feature Selection

Feature Selection is used to limit the rare features once again similar to many Machine Learning techniques.

Vectorization

In the vectorization stage, structural multimaps are first replaced by structural maps—ordinary map data structures that map a structural path to a corresponding single numeric value. To this end, every set of values corresponding to one structural path in the multimap is reduced to its median.

Learning and Classification

The authors have used Random Forest implementation at this stage. But, it can be any classifier as per reader’s choice.

Experimental evaluation

The authors run their experiment on two datasets, one for PDF and one for SWF file formats. Both of the datasets were collected from VirusTotal. A file is considered as malicious if it is labeled as malicious by at least five engines. Alternatively, a file is labeled benign by all antivirus engines. Following figure shows that HiDost performs better that the antivirus engines in the VirusTotal. It should be mentioned that VirusTotal may not contain the most efficient antivirus developed by the proprietor company.

Machine Learning on Malware is Hard

While machine learning algorithms have been successfully applied in various vision and natural language related tasks, they have not been fully successful in malware detection. The reasons are mainly three-fold:

High Cost of Error

In the case of malware detection, when measuring the performance of a classifier, both false positive rate and false negative rate are important factors. While the false positive rate means a benign software is classified as a malware, in the false negative case a malware is classified as benign. Both the events are undesirable for malware detection. Since, false positive requires excessive spending of a human analyst’s time which could be expensive and time consuming. On the other hand, false negative means a malware is left undetected, which can have serious security consequences. A typical machine learning model trained for the malware detection task tends to have non-zero false positive rates and false negative rates.

The above figure shows the example performance of a typical malware classifier (B) which has non-zero false positive rate, whereas an ideal classifier (A) would have zero false positive rate.

Semantic Gap

There is a disconnect between the prediction result of a machine learning model and the action to be taken based on the result. For instance, if a model predicts a malware with 65% confidence, what action should be taken? Should the target software be removed without intimation to the end user? Should the user be alerted for a manual inspection? In such a scenario, it is hard to interpret the results and take a meaningful action.

Difficulty with Evaluation

One of the major difficulty in the evaluation of malware detection tool is the availability of datasets. Most of the public datasets like Contagio or Drebin are small or outdated, whereas the malwares keep updating aggressively. It is difficult to create new rich malware datasets due to data privacy concerns and the labelling of malwares in the wild. This poses problem for training and evaluating the machine learning models.

Another difficulty is the evasiveness of the malwares. Malwares have become dynamic enough to evade the malware classifiers. Given a white-box access to the classifier, malware can perform adversarial training like gradient-based method to evade detection. Even with black-box access, the malware can perform mimicry attack by appending features of benign samples. Figure below shows an example of mimicry attack. The file on the right is a benign file and the file on the left is a malicious file. By appending some features from benign file to malicious file, the classifier can be fooled into accepting the malicious file as benign.

However, this may or may not break the malware’s functionality and hence it is hard to generate useful samples. One variant is to use reverse-mimicry attack by embedding malicious features into benign file to generate malicious samples as shown in the figure below.

Recent literature has also shown evasion by genetic mutation and hill climbing method, where the malware can dynamically adapt to evade detection.

In genetic mutation attack, adversarial malware samples are generated by repeated operations on the malware sample until it is accepted as a benign sample by the classifier. The operations are addition, deletion or replacement of benign file features to the malicious file. The process only requires a binary output by the classifier whether the input was classified as malicious or not.

In hill climbing method, malicious file is taken as input and all possible recursive variants are tried until the malicious file is accepted as benign by the classifier while the malicious functionality is retained by the file. In figure below, the state e is the end state where the process has found the required adversarial sample, and the process terminates.

Both the genetic mutation and hill climbing methods are shown to fool PDF Rate and Hidost malware classifiers.

State of the Art

Liang Tong, Bo Li, Chen Hajaj, Chaowei Xiao, Yevgeniy Vorobeychik, “Hardening Classifiers against Evasion: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” arXiv:1708.08327. August 2017. [PDF] [4]

Anti-malware defenders today attempt to passively analyze files of a specific type across the web and flag potential malware. These models are often trained offline. The counterparts to these software work much more actively to produce mis-classified malware. These attackers work against black box or often black-world (no response) classifiers.

Behavior Preservation

Malware behavior preservation is difficult due to the nature of code; most changes risk breaking the code entirely. This means that random mutation processes need to be heavily limited to preserve the behavior of the code. Mutation processes are often either trivial or not done at all. Very few papers allow mutations and verify the process afterward, as it requires dynamic analysis in a sandbox.

For this reason, malware development turns often to genetic development algorithms for finding evasive samples. The nature of these changes is more likely to preserve the behavior of the malware whilst creating a new sample that may be more evasive.

EvadeML

Malware development in search of evasive samples is often done using genetic algorithms mostly using greedy searches. EvadeML is one such development process to create evasive PDF malwares targeting Hidost and PDFrate. The software has a 100% success rate within 20 generations and works by mutating the raw PDFs.

The below graph plots the number of evasive specimen in a population of 500 malicious seeds against the generation using the above evolutionary method. As is readily apparent, evasive malicious samples are not only easy to produce using a small number of generations, but are also numerous. This calls into question the value of the classifiers that we are using to identify malicious code.

EvadeML is also working on a project that would ideally limit the featurespace, thus enabling better targetted classifiers. This is done via a process called feature squeezing. This process is primarily important in the filter sections displayed below, as the featurespace is limited to fewer variables to be passed through a model.

For each filter, a number of new features are selected as some function of the original feature set. This works similarly to the first layer of a neural network, except that there is more human involvement, other functions can be and are used, and that once the filter function has been created, it in unchanged during the model training process. These filters can be built from rounding/cutoff functions, input smoothing, simplifying color bit depth, and other functions that a neural net is generally incapable of creating naturally. The goal of these is to complement defensive methods and work directly to limit the potential of adversarial training.

Deep Learning

There’s a slight disconnect between security researchers and pure ML researchers, particularly those that are doing research into deep learning. The deep learning architectures that are being researched for malware deterction are multi-layer perception on preselected features and convolutional networks, but there are very few recurrent models.

Detection softwares are working to identify dynamic features more specifically in malware, as any static features of the code aren’t being triggered at runtime. This shift minimizes the attackers’ ability to mutate their code while maintaining functionality. This does, however, enable ‘time-bomb’ style malware, where certain malicious features are static until a certain datetime.

Future of the Field

While progress is being made in the field, there are a number of challenges that need to be met for malware detection and evasion to evolve. Much work has been done in the area of both static analysis and the mutation of static features. However, it’s clear that static analysis isn’t good enough for today’s tasks, and that effective detectors and mutators need to embrace dynamic features.

The more challenging goal of using a learning model to algorithmically mutate dynamic features that preserve the functionality of original code is a more complex problem. While achieving effective dynamic feature mutation isn’t currently feasible with today’s research, a step in the right direction will certainly involve selecting an appropriate deep learning architecture. Perhaps recurrent neural networks, which fit sequence modeling tasks well, could be useful.

Detectors must evolve as well. Research has shown that some dynamic analysis algorithms are detectable, and that sophisticated threats can delay malicious behavior until they are no longer in a sandboxed environment. Effectively learning from sandboxed data streams and system calls will open up a new front in the arms race between detector and attacker.

Ultimately, from simple to metamorphic viruses, malware has evolved into increasingly sophisticated threats. The field of adversarial malware detection has been evolving as well, as methods are developed that are increasingly effective at detecting malicious code. As the cutting edge of malware detection moves forward, we will see new fronts open up in the contest between malicious files and the algorithms that detect them.

— Team Nematode: \

Bargav Jayaraman, Guy “Jack” Verrier, Joshua Holtzman, Max Naylor, Nan Yang, Tanmoy Sen

References

[1] Babak Bashari Rad, Maslin Masrom, and Suhaimi Ibrahim, “Evolution of Computer Virus Concealment and Anti-Virus Techniques: A Short Survey.” IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 8, Issue 1. January 2011

[2] Babak Bashari Rad, Maslin Masrom, and Suhaimi Ibrahim, “Camouflage in Malware: from Encryption to Metamorphism.” IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.12 No.8. August 2012.

[3] Konrad Rieck, Thorsten Holz, Carsten Willems, Patrick Düssel, Pavel Laskov, “Learning and Classification of Malware Behavior.” 15th USENIX Security Symposium. 23 April 2008.

[4] Liang Tong, Bo Li, Chen Hajaj, Chaowei Xiao, Yevgeniy Vorobeychik, “Hardening Classifiers against Evasion: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” arXiv:1708.08327. August 2017.

[5] R. Sommer and V. Paxson, “Outside the Closed World: On Using Machine Learning for Network Intrusion Detection.” 2010 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, USA, 2010, pp. 305-316. May 2010.

[6] Weilin Xu, Yanjun Qi, and David Evans. “Automatically Evading Classifiers A Case Study on PDF Malware Classifiers.” Network and Distributed Systems Symposium 2016.

[7] Hung Dang, Yue Huang, and Ee-Chien Chang. “Evading Classifiers by Morphing in the Dark”. ACM CCS 2017.