Class 2: Privacy in Machine Learning

In today’s post we introduce some key concepts crucial to understanding the current state of privacy in machine learning. In a time where novel machine learning applications are seemingly announced weekly, privacy is becoming more relevant as learning algorithms play varied and sometimes critical roles in our lives. We introduce differential privacy and common ‘solutions’ that fail to protect individual privacy, explore membership inference attacks on blackbox machine learning models, and discuss a case study involving privacy in the field of pharmacogenetics, where machine learning models are used to guide patient treatment.

Membership inference attacks

Reza Shokri, Marco Stronati, Congzheng Song, and Vitaly Shmatikov. Membership Inference Attacks Against Machine Learning Models. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (“Oakland”) 2017. [PDF]

Shokri et al. attempt to attack black box machine learning models based on subtle data leaks based on the outputs. If the membership of a datapoint can be identified in the training set of a black box machine, it poses a significant privacy risk to the data of users of machine learning services. This is especially important for machine learning services such as Google Prediction and Amazon ML, as an inability to guarantee the privacy of training data would preclude a significant number of customers from using their services.

The attack is based on the idea that there are noticeable patterns in outputs when the input is given to the model as training data. While no human would be able to pick up on a pattern of that nature, a machine learning model with a theoretically limitless data source has that power. As the purpose of machine learning is to notice and evaluate patterns beyond human recognition, using a machine learning model to attack black box machine learning models makes sense.

For a machine learning model to attack the black box, it first needs to train against other models where it can verify its own accuracy. For this, similar models need to be created for evaluation. These models are called shadow models, and need to be trained on similar sample data to the original model. To generate training data, these models use hill climbing methods on the black box to seek high confidence areas. By then sampling data using a simple distribution about those points, somewhat accurate training sets can be created. Ideally, these sets will be roughly the same size and distribution of the target model.

The attack model is then trained on a set of shadow models, using classifications based on whether or not the datapoint was in the training set of the shadow model. This theoretically works based on the attack model being able to locate areas in which the curves are overfitted in the shadow models and translate that into membership. Ultimately, the study produced results that ranged from 70% to 95% precision overall based on the target model. The model gave nearly no false negatives.

To limit the power of these attacks, more regularization can be used to minimize overfitting, as the overfitting patterns become less apparent as the curve fitting is minimized. However, differential privacy is the more general class of solutions that is the defining foundation of the current state of the field of privacy in machine learning.

Differential privacy

With the explosion of data collection from various social platforms and the increasing usage of machine learning on personalized applications like personalized medication, medical diagnostics, genomics and face recognition, the collection of sensitive human data is inevitable. When dealing with personal information, it is paramount to preserve the privacy of any individual participating in the data set. In a word, it is necessary to ensure that an adversary does not learn about the presence or absence of any individual’s information from looking at the synopsis of the data set. This goal is the central motivation the concept of differential privacy.

To fully appreciate differential privacy, let us discuss some alternative solutions to preserving individual privacy in a data set identify how each one fails in achieving the goal of privacy.

Failed alternatives

1. Allowing only group queries

It seems intuitive that individual data privacy can be preserved by restricting a user to only group queries. For example, a group query can be: “How many students in this class earned an A?”. But this blatantly violates the privacy if the user also queries “How many students in this class apart from Rick earned an A?”, where the end user can know if Rick received an A or not based on the answer to the two queries.

2. Add random noise to the query result

Adding random noise to the query result tends to obfuscate the relation between the input and the output, but an adversary can determine the noise distribution by repeated querying. Hence, this approach also fails.

3. Deterministic perturbation in answering

We can deterministically map every output to another value in the vector space to obfuscate the input-output relation. But this becomes far too computationally complex in a high-dimensional regime.

4. Withholding sensitive information

An easy, straightforward notion is to simply withhold any sensitive data before executing any query; however, this very action reveals information about the presence or absence of sensitive data.

5. Make output independent of any individual record

This approach certainly does not reveal the presence or absence of an individual in the data set. But this method is not of any practical use since, by mathematical induction, the output does not depend on the data set itself.

6. K-anonymity

Another way to achieve obfuscation of a record is to group it with \(k\) other records for each attribute. Unfortunately, this method also fails in high-dimensional cases, where it has been shown to be feasible to still distinguish an individual record.

7. Semantic Security

Semantic security is a strict notion in cryptography which ensures that the advantage of an adversary with an auxiliary information should be cryptographically small with or without the access to the output (ciphertext). In our query model, this definition is too strong and does not allow learning any useful information from the data set.

Defining differential privacy

The formal definition of differential privacy is given as:

A randomized computation \(M\) satisfies \(\epsilon\)-differential privacy if for any adjacent data sets \(x\) and \(x’\), and any subset \(C\) of possible outcomes \(Range(M)\),

$$Pr[M(x) \in C] \leq \exp(\epsilon) \times Pr[M(x’) \in C]$$

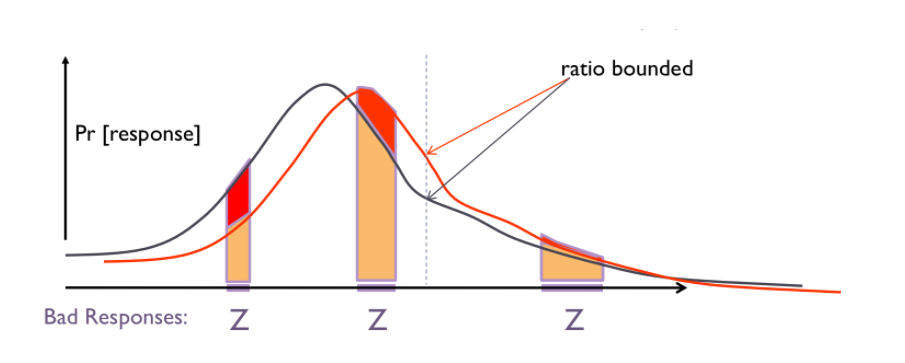

In other words, this means that the chance that an event occurs with your data and the chance it would occur without your data is closely bounded by a privacy budget \(\epsilon\). The figure below depicts the equation where the two lines denote the probability distribution over \(x\) and \(x’\).

There is another relaxed version of the above definition of differential privacy, called \((\epsilon,\delta)\)-differential privacy, defined as below:

A randomized computation \(M\) satisfies \((\epsilon,\delta)\)-differential privacy if for any adjacent data sets \(x\) and \(x’\), and any subset \(C\) of possible outcomes \(Range(M)\),

$$Pr[M(x) \in C] \leq \exp(\epsilon) \times Pr[M(x’) \in C] + \delta$$

The above definition basically implies that with probability \((1-\delta)\), \(M\) preserves \(\epsilon\)-differential privacy.

Properties of differential privacy

Group Privacy: An \(\epsilon\)-differentially private algorithm can be extended to provide group privacy for a group size of \(k\) by scaling the privacy budget to \(k\epsilon\).

Composition: Composition of \(k \epsilon\)-differential privacy and \((\epsilon,\delta)\)-differential privacy methods leads to \(k \epsilon\)-differential privacy and \((k \epsilon, k \delta)\)-differential privacy methods respectively.

Differential privacy with Laplace noise

To ensure \(\epsilon\)-differential privacy for a function \(f(x)\), we can add Laplace noise to it:

$$ f(x) + \text{Laplace}(0, \sigma)^d $$

where \(\Delta f = \text{max} || f(x)-f(x’) ||_1 \) and \(\sigma \geq \frac{\Delta f}{\epsilon}\).

Let us consider a working example. Consider that there are two adjacent data sets \(D\) and \(D’\) consisting of scores of students of a class, such that \(D\) and \(D’\) differ by only one student’s record.

Consider the function \(f\) that computes the class average. If, say, the minimum and maximum attainable scores are \(0\) and \(100\) respectively, then the sensitivity of \(f\) is \( \frac{100-0}{4} = 25\).

Thus, to release the class average of \(D\) is given by \(\frac{65+83+77+56}{4}\) with \(\epsilon\)-differential privacy, we would add the result of sampling \(\text{Laplace}(0, \frac{25}{\epsilon})\) to the computed value. This preserves the privacy of the student differing in \(D\) and \(D’\).

Privacy in Pharmacogenetics

Matthew Fredrikson, Eric Lantz, Eric and Jha, Somesh and Lin, Simon and Page, David and Ristenpart, Thomas Privacy in Pharmacogenetics: An End-to-End Case Study of Personalized Warfarin Dosing. USENIX Security Symposium 2014. [PDF]

In their case study, Fredrikson et al. analyze personalized Warfarin doses, a widely used anticoagulant. Finding the correct dose of Warfarin is vitally important as both low and high doses may result in death of the patient – literally, a matter of life and death.

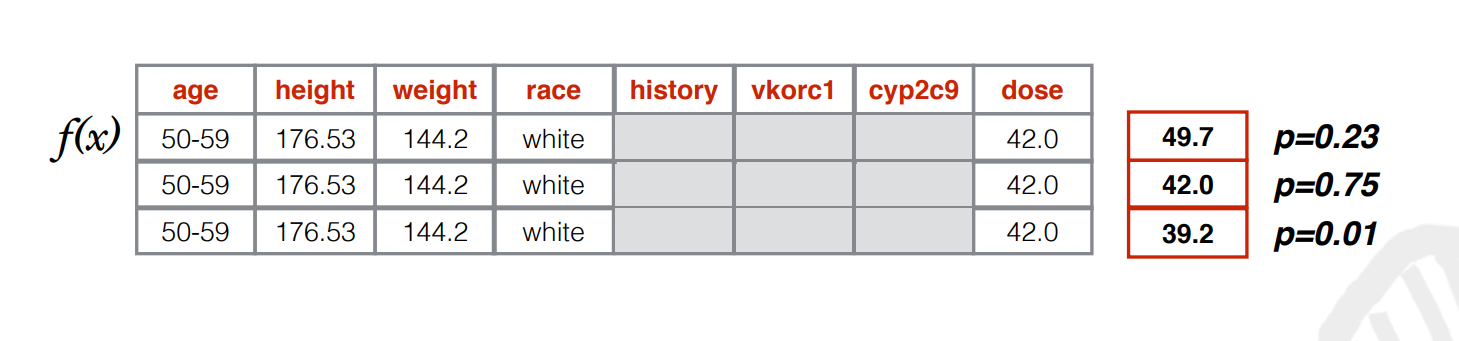

This experiment was done on the available IWPC dataset which contains and uses demographic information (age, height, weight, race), genetic markers (CYP2C9/VKORC1) and clinical histories of people around the world to predict their appropriate Warfarin dose. The IWPC has found that linear regression is the best learning model to fit the data and has made the model available for physicians’ use in calculating the initial dose of the Warfarin.

Let’s highlight how an adversary can use model inversion attack to violate the genomic privacy of a patient. We first initially assume that an adversary has black-box access to the trained model. As it turns out, due to the highly linear nature of the data, by running the model backwards, the sensitive genotype can be predicted given the stable dose of Warfarin, some basic demographic facts regarding the patient, and the marginal priors of the patient distribution.

How does the attack work? First, the adversary computes all the values of the missing variables that could potentially agree with the given information. Then, the adversary runs the model forward for each hypothetical patient in the dataset to predict the stable Warfarin doses. Finally, the adversary performs a likelihood computation to find out which configuration of the missing variables are most probable. Given the information and model inversion setting, this algorithm is optimal, as it minimizes the adversaries misprediction rate. With respect to the baseline, the accuracy of the model inversion attack is only 5% lower in comparison to ideal prediction.

As seen in this image, the attacker computes the values of missing variables, then predicts the Warfarin doses; and finally, using this information, finds the most likely configuration.

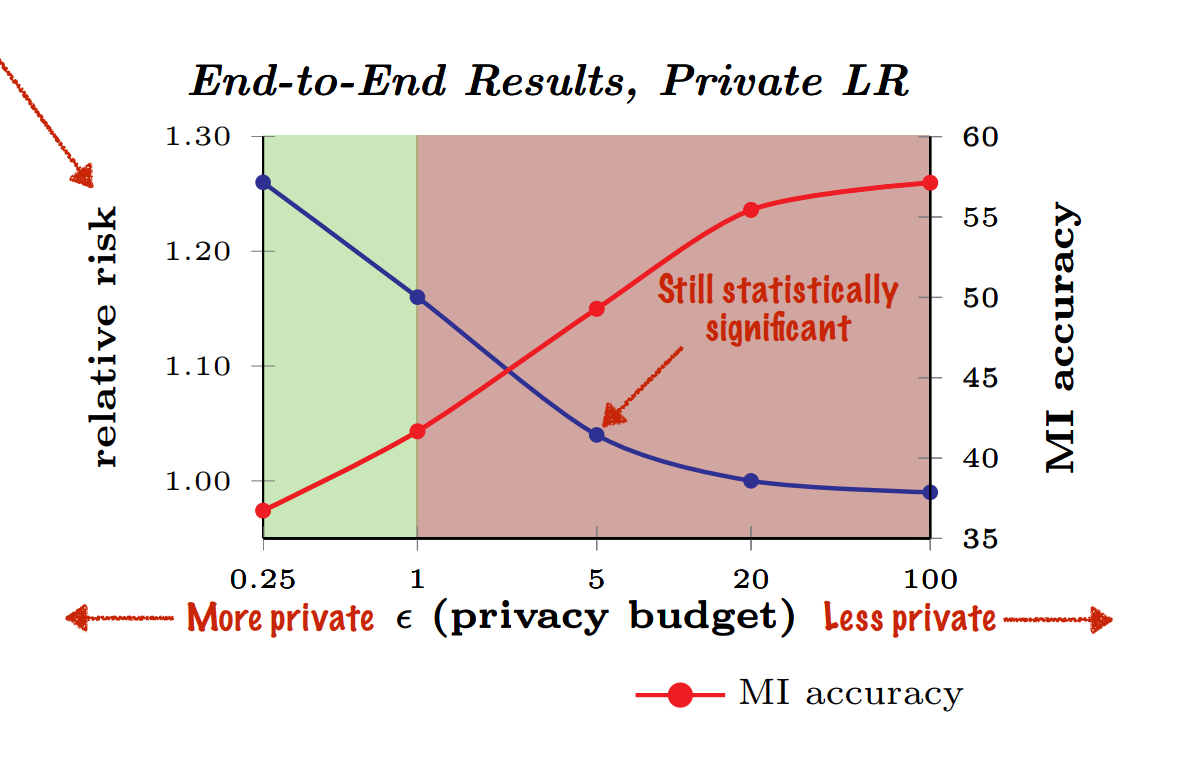

Adding noise using differential privacy strategy can be a countermeasure against the model inversion attack. But using differential privacy decreases the utility of the trained model. Based on their simulated trials, authors claim that there is no such privacy budget that can prevent model inversion, without introducing risk of overfixed dosing.

The Netflix Prize: Semi-supervised deep learning from private training data

Frank McSherry and Ilya Mironov, Differentially Private Recommender Systems: Building Privacy into the Netflix Prize Contenders. KDD 2009. [PDF]

Traditional recommender systems are usually not designed with an emphasis on privacy, which can be detrimental when the adversary are able to create multiple accounts to affect the recommendation at will. Researchers have been successful in developing powerful attack linking records in the Netflix Prize data set with other public user data. The implication is that sensitive information as the input of a recommender system can be linked and made inference about. Similar practical examples include making inference about purchase history through Amazon’s recommendations.

McSherry and Mironov’s paper adapted the leading recommendation algorithms (factor models and neighborhood models) to the differential privacy framework in order to develop a recommender system based on the Netflix data set while providing privacy guarantees. As mentioned in the above section, differential privacy enables privacy preserving computation by substantially precluding inference from the output data, unlike the prior efforts focusing mainly on cryptographic solutions that limit access to data of users. By doing so, it is conceivable that more uncertainty/noise is added to computation.

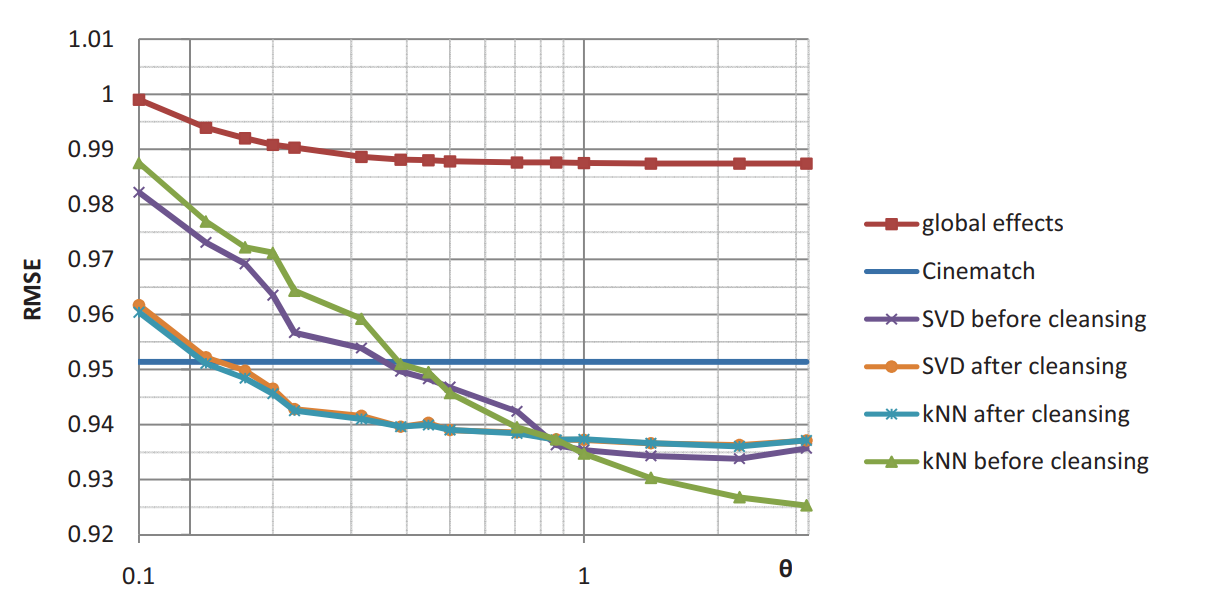

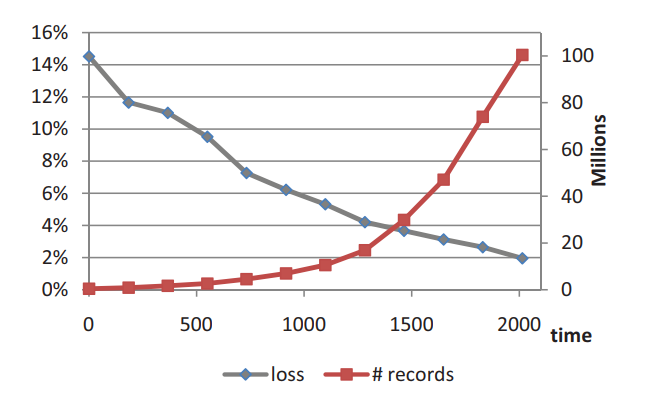

One interesting aspect this paper dealt with is the privacy vs. accuracy tradeoff. Evaluation of their approach was applied to the Netflix Prize data set which bears extremely high dimensionality. The root mean squared error (RMSE) was used as the metric for accuracy. The findings are as the quality of privacy increases, the accuracy of the recommendation drops.

Privacy vs. accuracy over time was also studied to explore how the loss of accuracy due to privacy-preserving decreased as more data become available for a fixed value of the privacy parameter. The results are summarized in the following figure.

Conclusion

We have introduced differential privacy and formally defined what is meant by preservation of \(\epsilon\)-differential privacy; discussed common solutions and how they fail; explained the properties of a differentially private algorithm, and how adding Laplace Noise enables \(\epsilon\)-differential private functions. We also discussed how in Membership Inference Attacks Against Machine Learning Models, Shokri et al. discuss attacking a black box model by training on a set of shadow models. Finally, we discussed how in Privacy in Pharmacogenetics: An End-to-End Case Study of Personalized Warfarin Dosing Fredrikson et al. demonstrate how a model inversion attack can be employed to infer patient genotype information.

— Team Nematode: \

Bargav Jayaraman, Guy “Jack” Verrier, Joshua Holtzman, Max Naylor, Nan Yang, Tanmoy Sen

References

[1] R. Shokri, M. Stronati, C. Song, V. Shmatikov, “Membership Inference Attacks Against Machine Learning Models.” May 2017.

[2] M. Fredrikson, E. Lantz, S. Jha, S. Lin, D. Page, T. Ristenpart, “Privacy in Pharmacogenetics: An End-to-End Case Study of Personalized Warfarin Dosing.” August 2014.

[3] F. McSherry, I. Mironov, “Differentially Private Recommender Systems: Building Privacy into the Netflix Prize Contenders.” June 2009.

[4] A. Narayanan, V. Shmatikov, “Robust De-anonymization of Large Sparse Datasets.” May 2008.

[5] J. A. Calandrino, A. Kilzer, A. Narayanan, E. W. Felten, V. Shmatikov, “‘You Might Also Like’: Privacy Risks of Collaborative Filtering.” May 2011.

[6] C. Dwork, “Differential Privacy and Pan-Private Algorithms.” August 2016.

[7] C. Dwork, “Differential Privacy - Lecture 1”. August 2016.